Christopher Cain: The Life Work of a Gerontologist

Gerontology, the study of aging and older adults, offers insights that go beyond medicine, encompassing psychological, social, and economic dimensions. From influencing public policies to innovating in elder care, gerontologists play a central role. As Christopher Cain knows, their work spans research, education, direct service, and policies. Whether it’s through designing accessible environments, developing age-friendly technologies, or addressing social isolation, gerontology ensures that longevity is accompanied by quality of life.

The Role of a Gerontologist

Gerontologists study the aging process and work to understand how physical, mental, and social changes affect individuals as they grow older. Their focus spans not just individual health but broader societal impacts of aging populations.

Unlike geriatrics, which deals with the medical care of older adults, gerontology looks at aging from multiple angles, including biological changes, psychological development, and social dynamics. Some may work in hospitals or clinics, while others contribute through academic research, policy analysis, or community outreach programs. Their efforts help inform better practices in caregiving and long-term support.

In university settings, gerontologists might conduct studies on cognitive decline or design programs that promote aging in place. Others may collaborate with nonprofit organizations to improve the quality of life for seniors in overlooked communities.

Why Gerontology Is Essential Today

As life expectancy continues to rise, societies around the world are facing new challenges tied to aging populations. The growing number of older adults means increased demand for services, research, and professionals who understand the complexities of aging. Gerontology plays a vital role in preparing communities to meet these needs with compassion and efficiency.

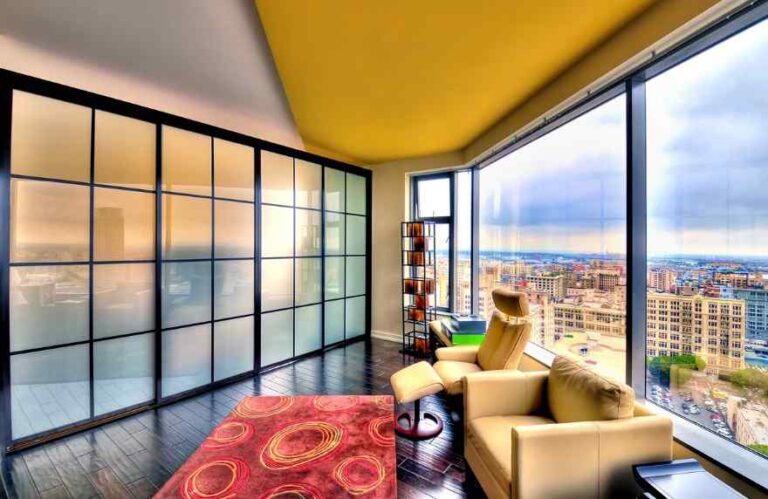

The field also contributes to shaping public health strategies, senior housing policies, and long-term care planning. By studying aging trends, gerontologists can help cities and healthcare systems adapt to the needs of older residents, ensuring they maintain independence and dignity. Communities benefit when older adults remain active and engaged, supported by systems built with aging in mind.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Work

A typical day for a gerontologist can vary widely depending on their specialty. Some professionals spend their time in research labs, analyzing data on memory loss or mobility issues. Others might meet with older adults and their families to create care plans tailored to individual needs. Their routines often involve clinical observation and administrative coordination.

In community health settings, gerontologists often work with local programs to improve access to services like transportation, nutritional guidance, or social engagement activities. Those in academic roles may teach courses on aging or mentor students pursuing careers in elder care. Their work bridges multiple disciplines, requiring collaboration with doctors, social workers, and public policy experts. This interdisciplinary nature allows them to impact individuals and systems simultaneously.

Education, Certification, and Career Preparation

Becoming a gerontologist typically begins with formal study in disciplines like psychology, public health, or biology. Undergraduate and graduate programs often include coursework on aging processes, lifespan development, and health policy. Many students also gain experience through internships at senior centers, research institutions, or clinics.

Some pursue advanced degrees to specialize in areas such as dementia care, aging policy, or senior advocacy. Professional certifications and ongoing education help keep practitioners current with emerging research and best practices. These credentials also signal a commitment to excellence in a field that demands both scientific insight and human connection.

Skills That Support Success

Successful gerontologists bring a mix of technical knowledge and interpersonal sensitivity. They need to communicate complex information clearly while showing empathy toward individuals facing the challenges of aging. In many situations, professionals must navigate family dynamics, ethical dilemmas, and shifting care plans. The ability to adapt, think critically, and work across disciplines is essential. Whether coordinating with healthcare teams or advising policymakers, these skills help bridge gaps and foster meaningful change.

Outlook and Opportunities

The future of gerontology is being shaped by rapid shifts in technology, healthcare, and demographics. Innovations like telehealth, smart home devices, and AI-driven diagnostics are changing how older adults receive care and maintain independence. Gerontologists play a key role in evaluating these tools and ensuring they meet real-world needs. As ageism and workforce shortages continue to impact elder care, the demand for well-trained professionals remains high.